It’s been more than a decade since Mike started writing these annual trend roundups while he was news editor at Game Informer. Since then, we’ve seen huge, unprecedented growth in the video game industry, new companies emerge from the shadows, titans fall, and entirely unexpected entrants make huge, paradigm-shifting waves.

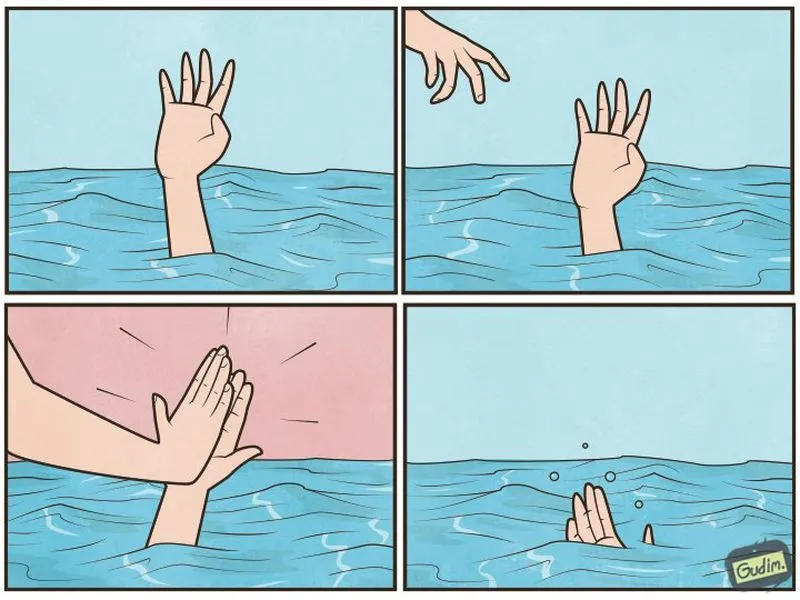

Right now, we are in one of the most trying times for the video game industry we’ve ever seen. There have been approximately 34,000 jobs lost since the start of 2022. Rampant consolidation, bad bets from the C-Suite, and over-reliance on Games as a Service have put pressure on labor across the industry, from AAA all the way down the budget scale to indie studios.

It is with optimism and hope that we look ahead to 2025, while we recap just what happened in 2024 to cause so much hurt and pain to so many. Will this year see the turnaround we so drastically need? Read on for our thoughts.

And, if you want to see where we were at this time last year, you can read our previous trends roundup here.

Additionally, we authored an academic journal article for ACM about the state of the industry. Mike was also published on GamesIndustry.biz on the topic.

Looking Back at 2024

Labor is the biggest story for the third year in a row

As we mentioned in the intro, there is nothing that defined 2024 more than the staggering job losses in the video game industry. We estimate that in 2022, 8,500 jobs were lost. That climbed to 11,500 or so in 2023. In 2024, we estimate that 14,000 people have been laid off. And those painful cuts have come in a number of different forms.

Of course, the predominant flavor of job loss has been outright layoffs. LinkedIn is a bloodbath. Every other day in 2024, we heard about another publisher or developer laying off staff, restructuring, or closing their doors. The casualties of the past few years are going to shape the industry for at least the next decade, with nearly one-third of juniors giving up on the industry entirely according to a survey conducted by InGame Job. This is by far the largest group affected, followed by mid-levels and seniors. According to the survey, 10% of respondents have exited the field during the waves of layoffs.

Those that are sticking around are struggling to find employment. 24.4% of those that answered the survey took three to six months to find a new job. 12.3% took more than six months, but less than a year. 8.1% of respondents to the InGame Job survey were (or are) out of work for more than a year. Put bluntly: we’ve never seen a situation this bad. To make matters worse, because it’s an employer’s market, salaries are dipping for those that make it to the end of an ultra-competitive hiring gauntlet.

Of course, we’re also seeing a couple of different types of “soft layoffs” hitting the industry. One is the infamous “RTO policy” or “Return to Work mandate”. After a necessary shift to remote work during the COVID-19 lockdown, the economic downturn caused by inflation, the invasion in Ukraine, and the genocide in Palestine has driven companies to squeeze every dollar they can to “return value to shareholders.”

One way to manage both sides of the balance sheet is through tax deductions and credits tied to corporate real estate. This is a driving force behind the return-to-office movement we’re seeing across industries. While big companies are ensuring their tax benefits are safe, they are offloading commuting time and costs to labor. And, in case you were wondering, commuting costs are not tax deductible.

The result is that some employees, especially those unwilling to relocate due to the instability of the job market or simply to preserve their family’s environment, are forced to leave. This is by design. It’s another way to reduce headcount.

Another trick companies are using in conjunction with layoffs and RTO mandates are buyouts. This one has recently hit a number of Ziff Davis properties, including GamesIndustry.biz (which appears to be down to one full-time staffer), IGN, and Humble. This leads us into our next trend…

Game Journalism is on Life Support

We need a vibrant and educated industry press. It’s that simple.

Especially in an era of massive consolidation of power, it is far too easy for large players to enact policy that is consumer unfriendly. We know that power structures in the video game industry have been rife with abuse at studios of all sizes. And the reason we know these things is that there has been a cadre of reporters doing meaningful, substantive, and illuminating investigative reporting.

In its early era, game journalism was mostly fluff. But in recent years, as the interactive medium has matured, so has the body that reports on it. While previews and reviews still matter, outlets continue to chase SEO and the elusive Google algorithm, which has further complicated visibility and awareness. Educated criticism and commentary, business-oriented journalism, and heartfelt interviews with creators have become powerful ways to tell stories. We’ve moved beyond the ‘what” of games and have matured to explore the “how” and why.”

The sad reality is that we’re taking massive steps backward. The scale and depth of coverage is not sustainable as outlets are forced by holding companies and flagging corporate interests to slice off limbs over and over again, ultimately leaving nothing but a brand without a body or soul.

This is a year in which we lost the oldest and last video game magazine in the United States, Game Informer. GamesIndustry.biz has been gutted following the sale from Reed Pop to Ziff Davis (along with VG247, Eurogamer, Rock Paper Shotgun, and Dicebreaker). Many of those outlets have already met the infamous Ziff scalpel. Key leaders in the IGN newsroom have been offered (and have taken) buyouts to ensure they have a small parachute before landing in a brutal employment warzone.

Consolidation has become a killer for everyone connected to the video game industry, including journalists and service providers. Ziff Davis is one of two titans in the space (PC Gamer and Edge owner Future being the other). As more outlets fall under these umbrellas, the diversity of voices and coverage dwindles. And, in the case of GamesIndustry.biz, we are at the precipice of losing one of the most important sources of industry knowledge in the modern media landscape.

And when new outlets, like Walmart-funded Restart, emerge and fund a small group of writers, it is met with derision by established media. While we understand the emotional response to a mega-corporation like Walmart funding an external content marketing company to create gaming coverage with affiliate links, the splash damage on hard-working, honest, and enthusiastic writers paints an ugly picture.

It’s hard as hell out there. It’s never been more challenging to be a game journalist. It isn’t going to get better as the creator economy has changed the calculus on communications. Why engage an impartial media when you can sponsor coverage that is almost assuredly going to be, at worst, neutral? Why risk opening yourself up to questions you aren’t comfortable answering when you can, instead, provide talking points?

If you value coverage that is independent from publishers and developers, read it and, when possible, pay for it. Because right now, a bulk of the audience is content to gift subs and splash bits during a live stream, but they aren’t willing to fund real journalism and criticism.

We need the games press. If we let the discipline die, we won’t realize how bad it is for consumers until it’s too late.

AAA is Learning the Wrong Lessons from the GaaSacre

When we started talking about the GaaSacre in 2023, we were hoping that AAA would look at what wasn’t working and pivot to something that had greater potential with lower risk (and potentially lower cost). Unfortunately, what we got instead was a combination of corporate “head meets sand” and doubling-down on what “worked” in the past.

The corporate engine is not well-tuned for being nimble. There are times, as with how Epic used to operate with Fortnite and even with EGS, where the 800-lb gorilla can function as the gazelle, but such corporate movement is rare. AAA games are monumental undertakings that cost hundreds of millions of dollars, take hundreds of (if not a thousand) developers and support staff, and often require anywhere between 5 to 10 years to move through pre-production to release. Turning that gigantic and deeply complex mechanism in the middle of a laborious process to begin with is nearly impossible.

That’s part of the reason why AAA is always, always late to the trends game. By the time a game gets out of pre-production, the trends have moved on and so have players. And at that point, there are only two options: press on or scrap the game. Once pre-pro wraps, the devs are locked in to the direction and while there’s some iteration on features, the direction isn’t likely going to change all that much (if at all).

So where does that leave AAA in the wake of everything going sideways all over the industry? Well, it leaves them in a rather precarious position, teetering at the edge of oblivion. A step back from the edge would mean that these studios (and publishers) would need to embrace experimentation, which is what AAA used to be known for, back before “returning value to shareholders in the short term” became the only corporate lever to pull.

Experimentation, especially at AAA scale, can be risky. But we would argue that staying the course and pretending that the past is the future is far, far riskier than a pivot. Instead of recognizing that we, as an industry, can make smaller bets (and therefore smaller investments) in more experimental or arthouse gaming experiences, AAA can only see the potential for glory in awards and the all-consuming notion of “number go up”.

The future is smaller, tighter, less expensive games made by smaller, tighter, more focused teams. AAA is going to either need to get on board or continue to hemorrhage time, talent, and treasure in the bleak hope that maybe, just maybe, this hero shooter will be the one.

The Funding Environment is Only Starting to Recover

If you’ve been following the news (or simply read the opening to this feature), you’ve likely heard about the vast number of independent studios laying people off, closing, or (dare we say) worse. Yes, there is something worse than these two things, and you need look no further than the way Jeff and Annie Strain have been accused of handling everything related to Possibility Space, Crop Circle, Prytania Media, Dawon Entertainment, and Fang & Claw. Yes… five companies that collapsed in short order this year.

Catastrophic mismanagement aside, many of the companies that have suffered over the last couple of years have been the victim of publisher derisking and equity funding squeamishness. On the publishing side of things, we’ve seen a massive shift of risk that has weighed down developers hoping to secure a deal to bring their games to market.

Prior to the post-COVID snapback, publishers and funders were willing to sign deals based on a pitch deck and prototype. Now, studios are expected to have a much more comprehensive playable and polished build (a vertical slice), an installed community to evidence consumer interest, and a plan for reaching the target audience. There are no guarantees in gaming, but those holding the purse strings want to get as close to one as possible before signing on the dotted line.

In speaking with Indie Megabooth founder and 1Up Ventures partner Kelly Wallick, we learned that early stage funding is starting to recover. While this is good news, we’re not yet seeing the same traction in mid- and late-stage funding. And we are starting to see studios hit the wall and come to a sudden, jarring stop.

Probably Monsters, which sold Firewalk Studios to PlayStation in April 2023, sunset two teams working on promising prototypes this year due to inability to secure funding. Two Mass Effect alumni, Mac Walters and Casey Hudson, both saw their studios (Worlds Untold and Humanoid Origin) shuttered. Countless others have told the same story, such that LinkedIn feels more like a graveyard than a professional networking site.

Right now, we have some optimism that recovery will accelerate in 2025, but there are no promises. There are so many unknowns related to global conflicts and the United States’ precarious political position that the winds could start blowing forcefully in the wrong direction.

But for now, we encourage independent developers to prioritize planning for bringing their own games to market without outside intervention. This leads us to our final trend for 2024…

Indies Can’t Rely on Publishing or External Funding

During the coronavirus pandemic boom, when we were all sheltering in place and working under quarantine, money in games flowed like spice on Arrakis — with some effort, but usually uninterrupted. Publishers and investors were hot on gaming like never before. We knew that there had to be a correction when the world began to open up again — because we live in an attention economy, among other things — but the brick wall that went up between developers and the money they need to keep their studios alive has been, well, painful.

As a result of this hastily built wall being thrown up, indie developers have been scrambling even more than usual. Even studios with signed publishing deals are no longer able to count that as “secure” funding, as publishers are pulling out of agreements all over the place. Between Private Division offloading nearly all of their portfolio, NetEase pulling funding support for their own western development studios (we’ll get to that), and even Humble Publishing crumbling under Ziff Davis’ weight… it’s been an ugly reckoning.

Before consolidation started gobbling up talent into the first-party and wholly-owned studio collections, publishers published games. They didn’t usually make games, but they worked with a lot of different studios on a recurring basis, cementing mutually beneficial deals that could span a number of years. Activision had a litany of games they published on a regular basis, with far more variety and appeal than the current Call of Duty roster of wholly-owned studios (now owned by Microsoft). These days, publishers act as holding companies for their wholly-owned studios, many of which are essentially internal co-development joints to support the corporation’s biggest priorities (Ultimate Team, CoD, Assassin’s Creed, Grand Theft Auto, etc.).

On the indie development side of the equation, funding is no longer providing the peace that it used to; it now comes with more strings than marketing dollars. The once solid promises that publishers were making to support indie developers are withering on the vine, unable (or unwilling) to make good on them, often citing “the market” as the reason why. Even studios with the appearances of unshakable funding — Jeff and Annie Strain’s failed game development “empire” comes to mind, as does NetEase’s western studios that are now closing at an alarming rate — and publishers with enormous warchests (Embracer Group) have proven that investment dollars are only as good as how you spend them.

With venture capital eyeballing the latest hotness (to them), whether that’s Web3 or GenAI, the chances of another “indie renaissance”, as we saw during the last big economic downturn in the late-2000s through the 2010s, are slim to nil. VC’s whole ethos is to cash in early when equity is cheap, raise lots of money, and then cash out with at least a 3x return on investment. For the most part, game development isn’t equipped for that. A lot of the time, our industry is a slow burn, akin to blockbuster motion picture development rather than the “big tech” that VC wants to believe we are. Without money, we’re either going to see alternative funding methods like crowdfunding (through BackerKit/Kickstarter) or patron models (through services like Patreon or Ko-Fi) keep game development moving.

Now, more than ever, indie studios are in a place where publishing money isn’t enough to secure the future of a title. As business strategists, we always advise studios to pull down money from multiple sources to try to mitigate that risk. Part of that can be in diversifying your studio’s revenue streams (what else are you and your team good at that you can market and sell?), but never underestimate the power of a grant. There aren’t a ton of grant options for game development in the United States, but if you’re making them elsewhere, chances are you’ll have access to more money than you realize.

Indies also need to rely on one another, whether that’s opening doors for fellow devs to remain financially solvent or sharing knowledge about the muckier bits of self-publishing. Now, more than ever, is the time for generosity and reciprocity.

Looking Ahead to 2025

“Survive to ‘25” Has Become “Survive Through ‘25”

Those in the industry that were saying “Survive to ‘25” are now going to need to rethink that strategy as ‘25 is here… and things aren’t exactly letting up. While we wouldn’t go so far as to say that 2025 is going to be worse than 2024… well, you know.

We’re only a handful of days into the new year and we’ve already seen studio closures and layoffs.

In our many conversations with developers across the game industry over the course of 2024, some indie and others in AAA studios, this refrain was running fairly strong. When we got to the autumn months, we all looked at what was behind us — wreckage — and what was ahead of us — probably more wreckage — and realized, “Oh no, the incoming year isn’t going to be better, is it?”

With an incoming American administration that will likely be hostile towards the entertainment sector (oh wait, that’s us) for a myriad of reasons, the threat of tariffs looming, and the economy barrelling towards a recession (thanks greedflation)… making games hasn’t felt this bad since the crash in the ‘80s.

As we discussed in our 2024 retrospective, funding is starting to recover, but only for seed rounds. Publishers and video game funders are more risk-averse than ever and are tightening their purse strings to the point of ineffectiveness. This leaves every single studio, even those with warchests of capital funding them, in a vulnerable position. What seemed like a surefire bet in previous years has become too risky to pursue. And building with new IP? In this economy? Unless you’ve got a few years of development runway in front of you (and you have the right people managing the budget with zeal), forget it. We’re in the Land of the Uninspired, folks.

While other analysts are out here saying that we’re anticipating a “return to form” in 2025, there is very little data to support that outside of trend analysis. Game announcements are not an indication of the health of the talent making the games, after all.

Here’s what we know: game developers are the most hopeful folks out there and hope isn’t a noun. It’s a verb. It’s active. As we said earlier in our retrospective, now is the time to band together and be generous with fellow developers, share resources, create more unions, and build collective knowledge. The only way we “Survive Through ‘25” is together.

AI’s Promises Won’t Be Kept

The magnificent life shifting pretty okay decent lackluster painfully destructive promises that unscrupulous, climate-denier techbros have made to our industry about how generative AI (genAI) will change how we make games — look at how fast we can prototype and how we no longer have to pay for any kind of art! — are, like many other things in Silicon Valley, riddled with holes and contradictions. (And usually a few -isms, just to make us all aware of how little they care for others.)

Whatever promises that have been sold up in the C-Suite have done much more harm than good. Now, this isn’t to say that LLMs (large learning models) and machine learning are bad, per se. However, most models are built on a pyramid of environmental destruction, moral duplicity, and creative bankruptcy to deliver content that exists in the intersection of grifting and straight up theft.

In other words: integrating genAI into video games cuts to the core of what makes video games what they are. Without artists, writers, programmers, designers, and the myriad disciplines that collaborate to create the worlds we play in, games will lack soul and heart. Unlike what the New York Times considers to be the driving economic force in gaming — graphics, naturally! — the look of a game (even if it dips into hyperrealism) isn’t what makes a game truly special. It’s the combination of brilliance and innovation that makes games what they are.

GenAI has the capability to rot the core of game development in order to err on the side of capitalism. Sure, games need to make money. We know this. We accept it. We even embrace it so that we can keep our studios alive and continue to reach our players with art that only we can make the way we make it. Cost-cutting of this scope (and scale) doesn’t work if players abandon the medium because it becomes full of AI slop. We would all be poorer for game development to move in that direction. It’s a runaway train driven by internet grifters and AI bandits.

AI has a place in game development. It’s how we improve processes, create more effective and efficient pipelines, and ensure that the fiddly work that no one wants to do is more automated, but not driven entirely by machines. These marginal improvements create more room for creativity and experimentation, which are essential elements of pre-production anyway.

But try telling that to an executive who just sees the bottom line and developers as a means to that end. Or, worse still, fellow creatives who don’t see the value in other disciplines, so why not outsource to computers?

AI doesn’t create games. People do.

Trump’s Tariffs Could Start an Economic Cold War

We’re not sure if the majority of America’s voters were asleep in social studies class or just have short memories. But for those of us who didn’t snooze through American History (or World History), we remember just how damaging tariffs are.

For those that aren’t aware of the intent and execution of tariffs, it works like this. The government imposes a surcharge on goods coming from certain territories. (In this case, the proposed tariffs are 25% on goods coming from Mexico and Canada and 10% on items coming in from China.) The manufacturer is required to pay the tariffs (not the country of origin, as many Americans erroneously believe).

These costs are almost always passed onto consumers in whole, or in part. That means prices are going to go up. We import lumber from Canada. We import produce from both our northern and southern neighbors. This isn’t just about the price of iPhones and PlayStations increasing. Our grocery bills, which have skyrocketed in the past couple of years, are likely to go up even more.

And, when we‘re still seeing massive layoffs across so many industries, including our own, this puts enormous additional pressure on families already struggling to make ends meet. As necessities increase in cost, luxury items (like gaming and other hobbies) tend to suffer. This is what the United States voted for, and it is practically unfathomable to anyone with half an eye on global economics that so many people voted so firmly against their own interests.

But, of course, it doesn’t stop there. Tariffs are viewed as economically hostile on the global stage. They are often met with retaliation. That means that any country that the incoming administration takes aim at will fire back with their own punitive economic actions. This is bad news for consumers around the world.

A gaming executive told me in a conversation at The Game Awards that we are fortunate that so much of the industry has moved from physical to digital distribution. This will help mute the impact of tariffs a bit, but it will also see indie developers (and publishers) slim down their physical releases even further. This will have a long-term ripple effect on preservation efforts. But for those games that do get physical releases, we may see some cost increases due to industry standard parity between physical and digital pricing for releases that offer both options.

Tabletop developers and publishers are facing a much harder road than their videogame colleagues. At PAX Unplugged, we spoke to a number of individuals about the potential of tariffs. Renegade Games marketing manager Jordan Gaeta told us that his company, which has strong relationships with both Hasbro and World of Darkness, is preparing in multiple ways.

Gaeta said that the company has multiple plans that account for “bad to worse” scenarios. In addition, Renegade is cutting costs in advance. The company had planned a bigger push into Europe with a Spiel Essen appearance in 2025, but has since delayed their plans to attend the world’s largest tabletop gaming show. Erin Zipperle, co-founder of Rollacrit (developers of Heroes of Barcadia and the beloved Bag of Holding) are exploring other ways to avoid the tariff pinch.

Zipperle tells us that his company, which was born from the ashes of GameStop-owned Think Geek, is looking to engage manufacturers outside of the known tariff zones. This includes conversations with manufacturers in Eastern Europe who can meet Rollacrit’s specific needs. Additionally, we’re seeing U.S.-based tabletop manufacturing slowly start to get on its feet in terms of paper products (cardboard, packaging, leaflets, etc.), but plastics are as of yet out of reach here. Those will continue to be imported, as there simply aren’t facilities here to support the volume and variety required for board game products.

This is likely to have a material impact on product design. Kickstarter has, for more than a decade now, been a way for board game designers to flood tables with intricate miniatures in huge numbers. The process of designing and bringing to market plastics-heavy games is extensive, with multiple iterations that tinker with molds and materials. With looming tariffs, we anticipate that miniatures will be phased out by some designers or be offered as crowdfunding-only additions that carry enormous extra costs. “Table presence” is about to become that much more costly.

We also anticipate that tabletop manufacturers will find ways to lean further into cost-saving digital expressions of their games. Roleplaying game publishers have a head start here thanks to the COVID-19 lockdown. Virtual Tabletops (VTTs) like Foundry and Roll20 were a way to keep people connected when they couldn’t sit at the same dining room table and roll dice. We’ve seen companies like Dire Wolf (Clank, Dune: Imperium) bring their catalog to digital devices and also help companies like Leder Games (Root) reach new audiences in that way.

Restoration Games, developer and publisher of the excellent Unmatched game, has brought that title to digital devices, also. It’s a smart way to engage new audiences and reinforce your brands and offerings with those already engaged.

As you can likely tell from all of the focus companies across gaming are giving the threat of new costs in an already strained economy, decision makers are worried. And, realistically and historically, tariffs just don’t work. They will hurt average consumers here and abroad and spark animosity with even our closest allies and neighbors. We can only hope that Wall Street executives who have the ear of key people in the administration can talk the incoming government out of this foolish course of action. Realistically, that hope is slim.

Privatization and Consolidation Are Still Looming Threats

There was a time that half of Virtual Economy was consumed by our Investment Interlude segment. During this portion of the podcast, we cover mergers and acquisitions and all the investments along the way.

During the COVID-19 gaming boom, Microsoft, Embracer, Sony, and so many others were gobbling up every studio, publishing business, and service agency they could. This FOMO-fueled expansion, which resembled a frenetic game of Hungry Hungry Hippos, was a major factor in the staggering layoffs we’re facing today.

And, now that inflation has created global economic hardship, the video game industry is realizing that its pandemic gains were merely a short reprieve. Now, we’re facing the contraction that every other industry faced during that period on top of the macroeconomic strain every other business is confronting.

And, still, we are seeing acquisitions happen that are cause for alarm. For instance, Leslie Benzies’ Build a Rocket Boy studio, which has not yet released its first title, just acquired developer PlayFusion. Keywords continues to acquire studios and service companies at a rapid pace. Dan Hauser’s Absurd Ventures is also spinning up a new team formed from the ashes of Immortals of Aveum developer Ascendant Studios, again with the former having not yet released its first game.

Every time we see news of an acquisition in this climate, we wince a bit. We’ve seen far too often over the past two years the cycle of acquisition to layoffs or outright shuttering. Studios gave up their independence for what they thought was security only to find their teams out in the cold during the worst labor crisis the industry has ever seen. Consolidation is crushing innovation and growth. It’s killing jobs, and talent is fleeing the field. We’re losing vast swaths of institutional memory held by seniors while also making it impossible for juniors to get a foothold. The industry is being devoured on both ends, setting us up for a long period of rebuilding once the global economy recovers.

We do not expect consolidation to slow much in 2025, as large corporation finances begin to recover while labor continues to struggle. There is a stark mismatch in the realities between those who lead gaming companies and the people who make the products those companies sell. Until that friction is resolved, the industry won’t be able to truly recover. Here’s hoping that 2025 brings a much-needed reality check. Decision makers must remember that without empowering and nurturing creatives, the audience will start to wander away.

Gen Z and Gen Alpha Aren’t Playing Games Like We Do… And This Could Be Trouble For AAA

All of our children are Gen Z (Zoomers) and there’s no single way to pin down the games that they all love to play. Our twentysomething daughter lives for nostalgia and adores LEGO games as a result. Our two teens play games very socially and prefer experiences that allow them to connect with friends (and family) through mutual creativity or shared gameplay. Our youngest, not quite a teen herself, is most aligned with how her parents play games. That is to say: she plays a lot of games and loves stories with a passion that both of her writer parents find endearing.

Their friends fall pretty neatly into these categories, too. But our youngest’s taste in games is no longer “the norm” driving her generation, which means that as Gen Z starts to age into more access to discretionary spending outside of their parents… their tastes will shape the future of what gaming is going to become. And AAA is not ready for that.

User-Generated Content (UGC) is going to be a key driving force, as many Gen Z (and almost all Gen Alpha) players have grown up on digital playgrounds like Fortnite, Roblox (despite its deeply problematic content moderation, or lack thereof), and Minecraft. They don’t just want ways to customize their experiences, they require it. It’s not about self-inserts in games, either. It’s about molding the game to their tastes, rather than have the game shape it for them.

UGC isn’t new to our space, of course. If we think back to the ‘90s and ‘00s, modders have been breaking and molding games for a long, long time. Heck, even Manda dabbled in Sims mods and crudely implemented UGC back in the ‘00s. What’s different here is that UGC is now something that is actively being paid for. In-game UGC purchases not only benefit the studio’s bottom line, but that of its creator as well. (Unless it’s Roblox, in which case it’s basically just scrip for the “company store”.)

Unreal Engine for Fortnite (UEFN) has quickly become a big part of the game development investment conversation, much like studios popped up around Roblox’s UGC (Adopt Me’s Uplift Games comes to mind there). There are a number of UEFN studios and development services that have popped up over the last couple of years, garnering some serious influx of venture capital on top of it. Since UEFN is still fairly fresh (not even two years after launch as of this writing), we don’t know how it’ll pay off. But, just like everything else, having a first-mover advantage over other developers who are waiting to see if UEFN is the Next Big Thing could really help these studios’ bottom lines.

But AAA, at least from the outside perspective, isn’t nimble enough to recognize their own trend-chasing isn’t working, let alone to understand that UGC is going to quite literally be the future of what Gen Z and Gen Alpha are going to be playing in the coming decades. Yes, tastes shift and change as we do, and that could happen here, but we can’t bank on the same old bets that AAA has been making, regardless. It’s not capturing the new reality of what players really want in their games.

There will always be room for great storytelling in games, especially in emergent narrative, but is there room for as many “this is my only game” live-service experiences as we currently have? Likely not. Preparing for the future of game development means understanding not just what players want, but staying on the bleeding edge of what they need.

AI can’t do that.

The C-Suite can’t do that.

Game developers will continue to do this, as they always have. The trends will trend, the shape of games will continue to evolve, but if anyone can reach into the collective psyche of their playerbases and pull out the “juice”, it’s game devs.